About a year and a half ago I began to get seriously into photography. I have always had (indeed, had to have) an artistic occupation that was separate from work, but which felt like more than a craft or a hobby. For a long time, I wrote poetry - I still do, though I feel less and less in touch with that side of things as time goes on. When I moved to Alberta I began seriously playing the mandolin, and was pretty obsessed with it for a number of years, but that dropped off too a few years ago. I still write and play occasionally, but poetry and music aren’t as central to my aesthetic life as they once were.

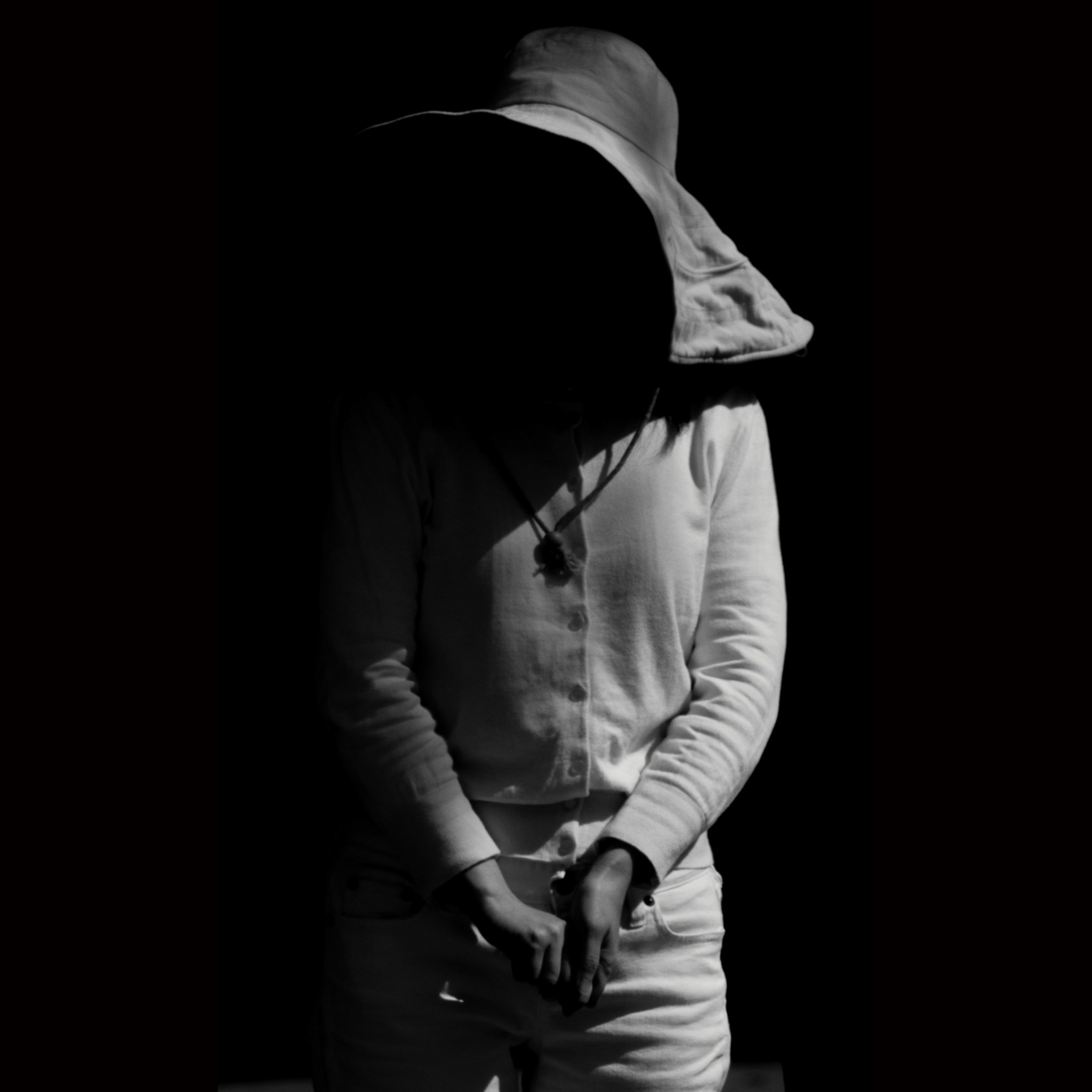

Photography poses its own challenges. By temperament I’m a formalist and I enjoy abstraction - perhaps this is why my poetry was never concrete enough for others, and why I appreciate purely instrumental music, with its absence of a referent. Photography, as the recording of some really existing thing, posed the problem of aesthetic abstraction, but that, I think, is purely a technical problem. Abstraction in photography can be approached similarly to the way figurative, pre-modern painters approached it, in the patterns and juxtapositions of light, shadow, texture, etc. For example, in the photo below, the image is still representational, but the abstract elements have been brought out in the high contrast between light and shadow, the enigmatic absence of the face.

A more challenging problem is proposed by the lack of the time dimension, the lack of duration. In poetry and in music, the artifact develops over time, grows and spreads and turns back on itself. The idea of rhythm in both poetry and music is a value of time which the photograph - as an instantaneous slice of reality - lacks. Sometimes the word “rhythm” is applied to the elements in a photograph, but I think this is a metaphor that is only partly applicable. The lack of the time elements is one of those “productive constraints” that all arts need, and photography - like all successful arts - makes a virtue of that necessity. Nevertheless the problem of development and resolution remains.

I see it as a problem because it seems to limit the capacity of photography to change the world. Perhaps this would be less of a problem if, over the course of photography’s history, we hadn’t placed such a weight of world-changing responsibility upon it. Photojournalism, documentary and conflict photography, Robert Frank’s Americans and the work of the Farm Security Administration, all seem to change the world by forcing us to see the world differently. But is this in fact possible without the movement of time? It seems, on the surface, as if photography must be the quintessential bourgeois art-form, slicing and isolating moments of time as if they were self-sufficient, atomistic, rather than elements of a longer and deeper flow of changing social reality. Photography, in this sense, seems bound by ideology in ways that other art forms perhaps are not. And the moving picture is no solution, since it has always been so comfortable with its commodity nature and the consumerism of its production and consumption.

In her 1977 book of essays On Photograph, Susan Sontag makes the following remark:

Marx reproached philosophy for only trying to understand the world rather than trying to change it. Photographers, operating with the terms of the Surrealist sensibility, suggest the vanity of even trying to understand the world and instead propose that we collect it.

If we follow Hegel, as Marx did, we have to recognize that the dimension of time is essential to true understanding. The process of dialectical tension, contradiction, and resolution is a temporal process, and without it, Sontag suggests, understanding is impossible. All that is left is a process of registration and classification, a process of cataloguing (parallels with librarianship crop up throughout Sontag’s critique of photography). But if we go further than understanding, to change, then we would have to, like Marx, set Hegel on his feet. Now we appear to be at a further remove from any potential for photography to at least assist in the transformation of the world.

It would be tempting to think of photographs as yet more arguments tossed into the ideological void, arguments marshalled against the bad-faith actors identified by Sartre whose role is not to reflect and understand, to see the world differently, but simply (like Dinesh D’Souza in his timewasting and distracting insistence on confirming Trump’s mispronunciation of “Thailand”) to keep the talk going, to exhaust, to wear down ethical positions through the weight of sheer, repetitious dishonesty. But we know that they have, in the past, borne a stronger evidential weight. Nick Ut’s photo of Phan Thị Kim Phúc, or Kevin Carter’s “Struggling Girl” are at the very least ethical testimony that change the world they are dropped into. They bear ethical consequences not only for the photographers (Kevin Carter committed suicide a year after taking the photo, and Don McCullin has always been very open about the questionable ethics of conflict photography and the toll it takes).

I think the element that Sontag misses is that time may appear to be stopped by a photograph, time may be a dimension absent from a photographed image, but time continues to flow in the world outside the photograph itself. The production and dissemination of an image is a temporal project. And more than that, photography, like all art, is unalienated labour, that is, it’s work. And all true work is part of a temporal metabolism with the material world, a back and forth, an ebb and flow of transformation and self-transformation. The dialectic may be absent from the frame, but the frame is part of the ongoing dialectic of our relations with each other and with the world around us.

Sontag speaks a lot about the alienating effect of photography, its voyeuristic and violating nature, its pretense at objectivity. And all of what she says about that is true: as a modern, technological art, photography takes part in the isolating and alienating nature of all capitalist technology. But like all art it is also and at the same time a social relationship and a piece of work. This contradiction cannot be resolved through thought or a change of perspective, it can only be resolved through a transformation of the social, economic, and political world itself. In the end, then, perhaps photography performs a vital service precisely in registering the contradictions, in fixing them in time, in totally preventing their resolution through narrative or discourse or functional harmony. (Here we have to remember the very bourgeois conception of harmonious resolution itself, and the ways in which Western classical music and the novel reinforced the bourgeois social order through their very forms and structures). Paradoxically perhaps, the fixed nature of the still image brings home to us the necessity and inevitability of temporal change; we see the nature of time most clearly when it is withdrawn, as it is in the photograph.

The photos of the Farm Security Administration show us a lost world, and it would be easy enough, as Sontag says, simply to “collect” such images. But if we pay attention to the way past time has been frozen, has been made unnaturally, eerily static, then the truth and necessity of historical transformation is made even clearer. A photograph, by capturing, fixing, and stopping time, reinforces the vitality of change, brings out the flux and ephemerality of being, and exposes political projects that imagine that time can be stopped (liberalism) or turned back (conservatism) as fools errands. Perhaps this is a productive connection between Marxism and photography which Sontag, from her vantage point as a child of the Welfare State was unable to see. She thought that photography was “too suffused with irony to be compatible with the twentieth century’s most seductive form of moralism”. Both irony and Marxism, however, have changed in the twenty-first century, as has philosophy. Perhaps all three have changed enough for photography to play the role Marx’s eleventh thesis on Feuerbach reserved for philosophy itself. But at any rate, it is enough for now that it scratches a particular aesthetic itch, satisfies a certain demand for unalienated work, that its larger importance can be set aside for a while to see how things, as they always do, turn out.