“… too high a price is asked for harmony; it’s beyond our means to pay so much to enter on it. And so I hasten to give back my entrance ticket, and if I am an honest man I am bound to give it back as soon as possible. And that I am doing. It’s not God that I don’t accept, Alyosha, only I most respectfully return him the ticket.”

Dostoyevsky, The Brothers Karamazov.

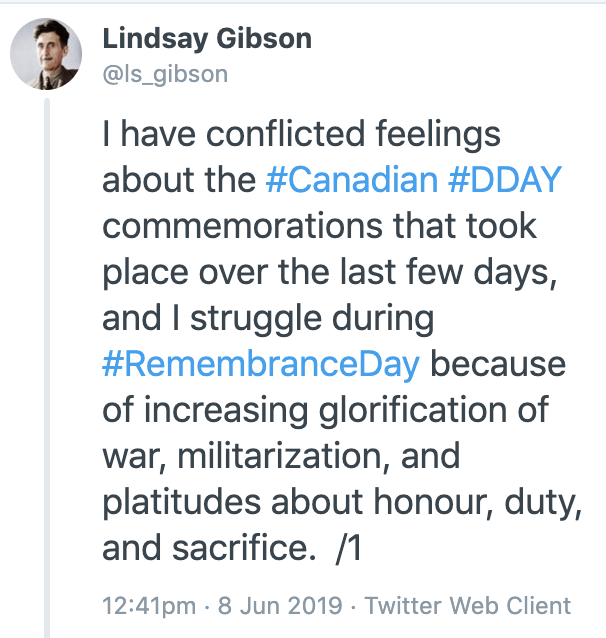

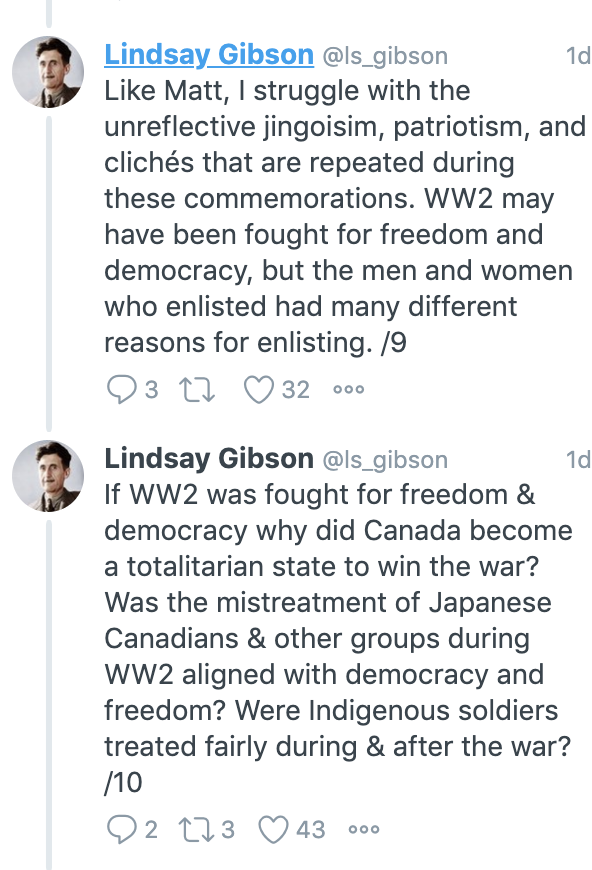

Since its inception, I have used this blog to think aloud and think through particular questions around technology, politics, and ethics. I have been pretty explicit about my own positions: the fundamentally exploitative and alienating (and unfixable) relationships of capitalism, the commitment to virtue ethics (as opposed to deontology or consequentialism), and the idea that both our social/political problems and their solutions are collective, not individual. But I haven’t spoken at all about a long-standing position which informs a lot of my politics: pacifism. In a sense, this is because pacifism is such a deeply-rooted foundation of my ethics that I hardly ever think about it explicitly, but also because pacifism raises issues (around the dictatorship of the proletariat, for example, but also around the idea of punching Nazis) that I haven’t particularly wanted to address. Last Thursday marked the 75th anniversary of D-Day, and last week also saw the release of the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls report, with its explicit judgement on Canadian history and society as genocidal. Commentary on D-Day thus mingles with commentary on the report and the various political contestations of the definition of genocide, so I thought some thinking out loud about pacifism might be in order.

There are various forms of pacifism, from so-called “contingent” or “just-war pacifism” which supports war in particular limited circumstances, through the anti-war pacifism which is not against violence in other forms, to non- and anti-violence either towards humans or towards all living creatures. I fall somewhere in the antiviolence towards humans category (I’m not vegan or vegetarian, and this raises its own ethical questions and problems). My pacifism stems, probably, from disgust at schoolyard and neighbourhood violence, and an anti-war stance was simply an extension of this; some pacifists, I imagine, start out holding anti-war positions and then either extend their pacifism to the more personal level, or not. But for me, pacifism begins with a hatred of individualized violence, a victim confronted with an attacker or a mob, and the anti-war position is simply an extension of that.

I’m making this point explicitly, because for me, the following position is incoherent:

“Increasing glorification of war” means that a certain amount of glorification of war is acceptable, that there is such a thing as just and honourable war, and that it is only when a certain tipping point is reached that war (or its glorification at any rate) becomes a problem.

The belief in a just and honourable war that becomes overly politicized or corrupted is a myth, just as the idea of a democratic Canada that became totalitarian is a myth. Capitalist, colonialist nations are never democratic, just as war - the slaughter of millions of human beings for the most tawdry of political reasons - is never just. “Just war” and “democratic state” are comforting lies we tell ourselves to hide our murderous, genocidal past from ourselves.

My great-grandfather, Ithel Davies, was a conscientious objector in the First World War, imprisoned in a military prison until he was beaten so badly that a question was raised in parliament and eventually COs were transferred to civilian jails. There is an unbroken line that connects the individualized violence of the imperialist state war machine and the one-on-one violence of “barracks justice”, just as there is an unbroken line that connects the individualized crimes of, say, Robert Picton, and the capitalist, colonialist Canadian state. A hatred of war and a hatred of crime go hand in hand, because war (even a one-sided war against powerless opposition, which is genocide) is the greatest crime.

Now, such pacifism raises direct political questions, especially for a Marxist. What do you with the capitalists? How do you “expropriate the expropriators” without violence? What is the dictatorship of the proletariat but the oppression/repression of the current ruling class in the name of a future justice. Is the dictatorship of the proletariat simply the “just war” myth of historical materialism?

I’m currently rereading Crime and Punishment which is directly concerned with these questions (since the question of the justification of revolutionary violence predates the Bolsheviks, and was a “cursed question” in the 1860s). Raskolnikov’s initial justification for the murder of the pawnbroker and her sister is “the greatest happiness of the greatest number”, that is a utilitarian rationality that has been used to justify enormous acts of violence, including those associated with the Bolshevik revolution, but also the colonial violence of the Canadian genocide (“kill the Indian in the child”), the Vietnam war (“we had to destroy the village in order to save it”), and the ongoing crimes and betrayals of the labour-capital relation the world over. This is the same kind of consequentialism that infects individual ethics: the end justifies the means. Dostoyevsky would rail against this idea in all of his greatest novels, but nowhere more strikingly than in Ivan Karamazov’s statement that if the cost of righteousness and a glorious future was the suffering of a single child, then he rejected such a future outright.

All this raises huge questions for me of political action, and the limits of political action, but I think that replacing a utilitarian consequentialism with deontological set of rules (such as, for example, United Nations conventions on warfare) simply evades the issue. The UN more or less legally enshrines the idea of a just war, an idea which I reject. And where is the UN on, for example, the Canadian genocide? The Canadian government ignores UN declarations with impunity.

I think Ivan Karamazov comes down on the side of a virtue ethics: what kind of human being do I want to be, and Dostoyevsky - albeit in a nationalist/conservative fashion - extends that to the religiously-constituted society. What constitutes the good society - not in the future, but now? This raises, as it should, a whole host of political questions around collective action, collective responsibility, collective power, and self-determination, but these are not questions that should be avoided. Myths such as the just war or capitalist democracy allow us to avoid those questions, but at the cost of handing over the ethical and political orientation of society to murderers, criminals, generals, and those who commit genocide.

I haven’t spoken here about wars of national liberation, guerilla wars against invaders, or whether there is any longer a useful distinction between physical and non-physical violence. Baharak Yousefi’s discussion of trauma in her closing keynote at the CAPAL conference last week raised the idea of widening and broadening the idea of trauma just as, perhaps, we need to widen and broaden the idea of genocide. These are all questions I have no answers to, but they are important questions to consider, and not only for pacifists.