Last year, I resolved - as a chronic book non-finisher - to finish reading as many books as I could. I didn’t particularly succeed at that, but I did manage to slog through some books to the end that I would ordinarily have given up on. This year, partly because I relaxed my resolution, and partly because I was doing a lot of “reading around” (articles, book chapters, sections), as part of my PhD planning, not only did I not read as many books to completion, but what I did finish were mainly relatively light distractions from the political theory I was concentrating on. Since I’ve been on research leave since August, I’ve also done a lot of writing, which contributes both to not reading quite as much, and reading a lot more lighter fiction as a way to unwind at the end of the day. Also, as opposed to last year, I didn’t resolve to write a review of each book I finished. I’ve therefore included some brief notes on each book here. I realize how many of these books are written by white men - I obviously have more to think about here.

Total books read: 24 (7 non-fiction; 17 fiction) This is only slightly down from 27 books read last year, but the breakdown is quite different. Last year, the majority were non-fiction (16 non-fiction; 11 fiction).

Emily Brontë, Wuthering Heights.

I really enjoyed this. Perhaps like most people, I inherited a lot of reading prejudices from my parents, and one of these was an antipathy towards the Brontës. It didn’t help that what I had picked up over the years about Wuthering Heights was that it was a Victorian romance novel - which is about as far from the truth as you can get. This is a wild ride: raw and violent and exceedingly modern. The people who live in and around Wuthering Heights are not genteel; even Jane Austen’s most despicable characters (i.e. everyone in Mansfield Park) hide it through gentility; in Wuthering Heights there’s no hiding how terrible most of the people in it are. At the same time, the novel seems to be precisely about how conditions of violence, cruelty, racism, and intolerance reproduce themselves from generation to generation.

E.M. Forster, A Room with a View.

This one was a bit slight. It was entertaining enough, but it didn’t really seem to add up to much.

Chester Brown, Louis Riel.

This graphic novel biography of Riel was really big when it first came out in 2003, but I passed over it at the time. It was OK, but neither the artwork nor the writing particularly did it for me. Again, it didn’t particularly offer anything of significance to the bare facts of Riel’s resistance, trial, and exectution.

Jeff Vandermeer, Annihilation.

I read this after seeing the movie, and because people whose taste in books I respect really like the whole trilogy. Again, it was fine, but didn’t do much for me. I have yet to read the second volume.

James Baldwin, Giovanni’s Room

This one was interesting for a number of reasons. I love reading Baldwin’s essays - there’s something about Baldwin’s language and turn of phrase that makes his writing really compelling even before you turn to the ideas he is expressing. Additionally, it was interesting to read what is essentially a Parisian ex-pat novel of the generation after, say, Henry Miller. The bloom is off the sexual rose by this time, and the whole story has a shadow cast over it that has little to do with the execution that lies at its heart.

Henry Miller, Quiet Days in Clichy (re-read).

Miller-Lite, if you like. A short novella covering a lot of the same ground as Tropic of Cancer, but with a certain darkness or nostalgia that I find a bit more interesting.

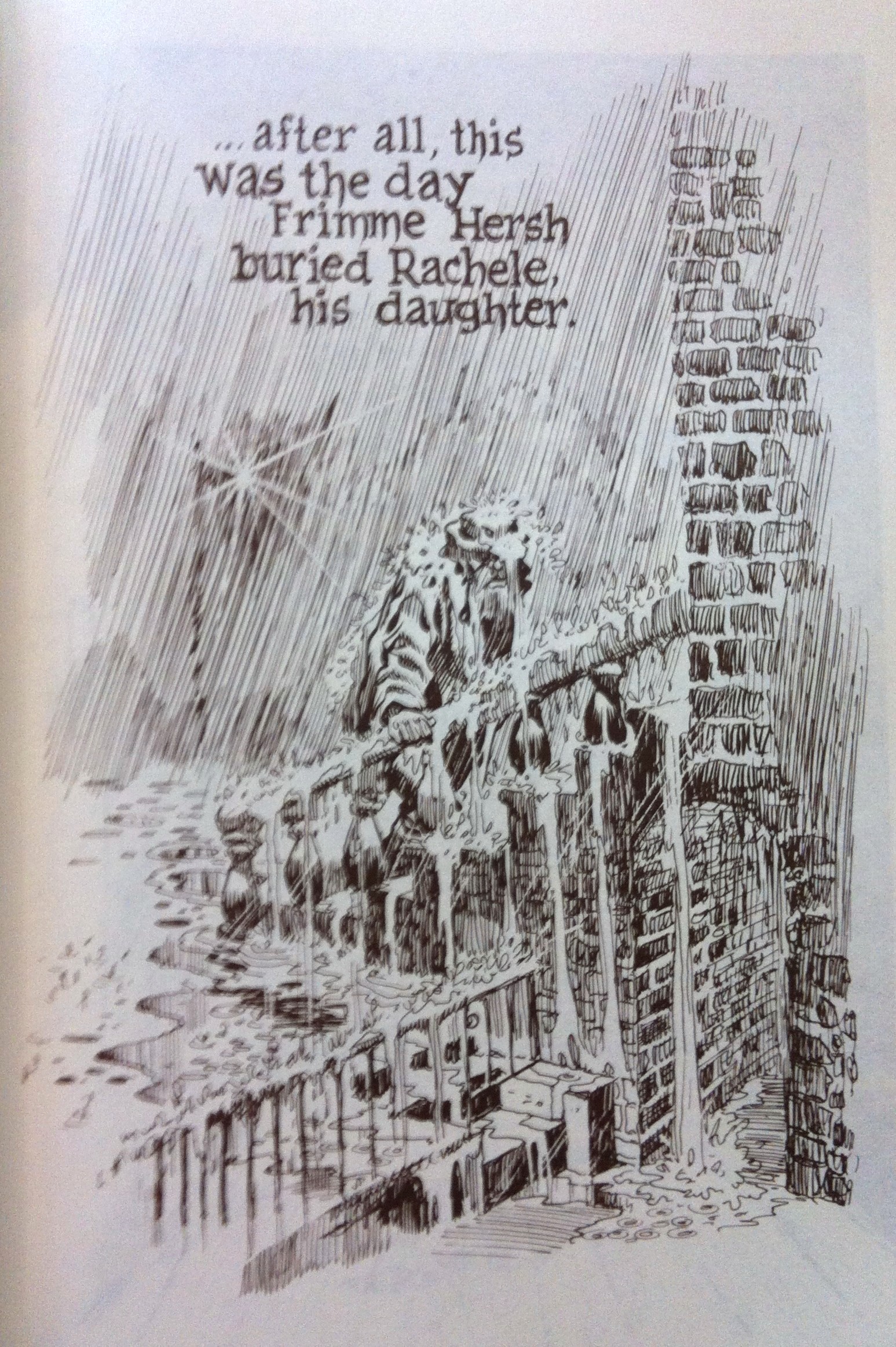

Will Eisner, A Contract with God.

Now this to me shows what graphic storytelling can do. Every page of artwork is stirring in a way that I found Chester Brown’s was not. It’s as if the drawing is in complete harmony with the text, supporting, reinforcing, and adding nuance and context to it. In the frame I’ve included below, the rain and the old man seem to flow together until you don’t know where one ends and the other begins, giving the whole thing a sense of eternal endless dreariness. The simple text (“… after all, this was the day Frimme Hersh buried Rachele, his daughter”) lets the image do most of the heavy lifting, allowing the text itself to make a virtue of its simplicity. The whole volume was fantastic to read.

Philip K. Dick. The Divine Invasion.

Part of Dick’s Valis trilogy (with Valis and The Transmigration of Timothy Archer, which I still have to read) and connected to the posthumously published Radio Free Albemuth, The Divine Invasion is Dick’s attempt to come to terms in fiction with the psycho-religious experiences that began in 1974, and which he poured into his Exegesis. What Dick actually thinks happened to him is not particularly clear, but it’s connected to a lot of the themes of his earlier fiction (the unstable nature of reality and our perceptions of it; a manichean view of good and evil, with our reality the creation of a devil or demiurge; the sense of struggle against evil unseen forces controlling the world…). Not up to the standards of Man in the High Castle or A Scanner Darkly, but fun to read nonetheless.

Robert Cormier, The Chocolate War (re-read).

I took some time this year to revisit writers I really liked as a kid. Cormier was always a writer who a) described a world of violence, cruelty, and intolerance that seemed much more real than a lot of other YA work at the time and b) didn’t condescend or sugarcoat anything for kids (see, for example, the horrific Fade). I think in some ways this is the appeal of Stephen King to a lot of teenagers (at least, this was true when I was in high school), but Cormier’s books are always firmly grounded in the real world.

Ursula K. LeGuin, The Dispossessed.

Le Guin died in January, and so many people I knew were talking about how much her writing meant to them, that I wondered why I had completely ignored her, even in my heaviest science-fiction phase. I was given a copy of Always Coming Home for Christmas when I was 12 or 13, but I couldn’t get into it - the ethnographic element was too dry for me. A few years later I read The Left Hand of Darkness, but didn’t feel compelled to read anything else. The Dispossessed is really great politically - it’s easy to see how it’s become an anarchist favourite - and I enjoyed reading it, but it still seemed to be missing something…? Anyway, I will read more to figure that out (I should probably reread Left Hand first).

Ian Fleming, Casino Royale (re-read).

This was just entertainment, something to read to clear Italian Marxist theory out of my head. I have a soft spot for the James Bond books because I grew up with them, but I wouldn’t recommend them to anyone (it will be interesting see whether Bond holds any kind of fascination for my nephews as they get older).

Michel Tremblay, Thérè et Pierrette à l’école des Saints-Anges.

Slowly working my way through Michel Trembley’s Chroniques du Plateau Mont-Royal, this is book two of six. I read the first volume last year (La grosse femme d’à coté est enceinte) and absolutely loved it - there’s a humanity to Tremblay married to amazing writing (both technically and stylistically) that manages to turn what seem on the face of it to be fairly prosaic accounts of working-class Montreal life into full and rich portraits of the development of real people. This second installment of the chronicles is just as good. I find it slow to read novels in French in Edmonton, when I’m not surrounded by la francophonie (I don’t have this problem in Montreal), but hopefully I’ll make it through another of Tremblay’s books in 2019.

Andreas Malm, The Progress of this Storm: Nature and Society in a Warming World.

A critique of different strands of contemporary social theory with respect to climate change and a compelling defense of historical materialism (Marxism) as the social theory we need right now. Highly recommended.

Kurt Vonnegut, Slaughterhouse Five.

I have been trying to read Vonnegut for years. A lot of people whose opinion I respect really get a lot out of him, but every time I tried to read him it all just felt too light, too frothy. I’m afraid Slaughterhouse Five, now that I’ve read the whole thing, is just more of the same. How do you make the firebombing of Dresden - an event which clearly deeply marked Vonnegut’s mind and emotions - seem… trivial? Maybe it’s just me - I don’t really get Vonnegut’s schtick. So it goes.

Maurizio Lazzarato, The Making of Indebted Man.

I read this as part of my PhD research. Very interesting, if a little slight - if you want to understand the financial crisis and the current culture of debt from a Marxist perspective, this is a worthwhile contribution.

Alan Garner, Elidor (re-read).

Another re-read from my childhood. I remembered Elidor being better than it was. It’s a darker, more working-class version of the Narnia idea, but it doesn’t really seem to pull it off. Garner’s The Owl Service is one of the best YA fantasy books I’ve ever read, but this one doesn’t live up to the memory I had of it, unfortunately.

Monica Hughes, The Keeper of the Isis Light (re-read).

I must have read all of Hughes’ science-fiction when I was a kid (at least, all that she had written up to that point - she kept publishing until 2002). I even enjoyed her non-SF work (My Name is Paula Popowich and Blaine’s Way especially). This one really lived up to what I remembered about it (which turned out to be more about setting and character than plot). It’s a bit dated now, but still worth reading; I have the other two books (The Guardian of Isis and The Isis Pedlar) in an omnibus volume from Edmonton Public Library, so I’ll try to read those again soon.

Philip K. Dick, The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch.

Apparently Dick thought that with this and Martian Time Slip he finally managed to figure out and pull off what he wanted to do in science fiction. Not as good as Man in the High Castle and very similar to Ubik - definitely worth reading for an introduction to Dick’s style and concerns.

C.S. Lewis, Mere Christianity.

Not having grown up religious at all, I’m interested in religions. This book is (apparently) one of the classics of Christian apologetics. I hated it. It was distasteful, intellectually dishonest, condescending, and the arguments didn’t hold water - at least, not from this side of the 20th century. I find it hard to believe that Lewis could not see the changes taking place in English society during and after the war; instead, he held to a white, patriarchal, aristocratic image of English Christianity that was never particularly accurate and nowadays seems dangerously archaic. If contemporary Christians are taking this as an example of apologetics (it continues to regularly make Christian “best book” lists), then no wonder it’s in such trouble.

Philip K. Dick, Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep (re-read).

This one starts out in classic (or typical) Dick style, but then becomes something else, something darker with more to say about human beings’ interior emotional lives as opposed to the the relationship between perception and reality. Apparently Dick wrote it in response to first person accounts written by Nazi guards in concentration camps which he read while researching Man in the High Castle. One of the constants in Dick’s writing is his very humanist empathy; in reading the guards’ accounts, Dick could not understand how human beings could feel/think/behave so inhumanly - he felt that perhaps they weren’t human at all, and so the idea of exploring the emotional distinctions between human and android was born.

Patrick Malcolmson, Richard Myers, Gerald Baier, and Thomas M.J. Bateman, The Canadian Regime: An Introduction to Parliamentary Government in Canada, Sixth Edition.

This is more of a textbook than anything else, but I read it cover to cover quite quickly. It’s really good on covering the details of Canadian government (what’s the difference between “responsible government” in Canada and “separation of powers” in the US?). It seems pretty exhaustive, and up to date (it covers the 2015 election, and goes into a decent amount of detail regarding the debate over proportional representation, for example). It’s interesting to read this as a Marxist, though, because the liberal presumptions and biases stick out like a sore thumb. Still, better to be transparent about that kind of thing than to appeal to some kind of neutrality.

Raymond Geuss, Philosophy and Real Politics.

I had heard of Geuss before, but I decided to read this based on a series of lectures on Nietzsche that he gave in 2013, which I found really informative (they’re up on YouTube). This book lays out the principles for “realism” in political philosophy, countering realism to various kinds of unrealistic theorizing - Geuss uses Nozick’s anarchism and Rawls’ theory of justice as examples of this - and makes the case for not relying on abstractions (“rights”, “justice”, “democracy”) when talking about politics, but actually looking at what people do in particular conjunctions. I’ll need to re-read this to make sense of it properly, but it helped clarify a bunch of things that had been floating through my mind.

Peter MacKinnon, University Commons Divided.

Basically lays out the hegemonic liberal conception of academic freedom, using a set of case studies from the last few years. Nothing particulary new here - I have a CJAL review forthcoming.

Raymond Geuss, Public Goods, Private Goods

Geuss continues his critique of liberalism by performing a “genealogy” of the concept of public and private. Looking first at three historical case studies (Diogenes of Sinope, Caesar, and St. Augustine) and the different ways they conceived of and problematized the distinction between the public and the private, Geuss moves on to critiquing liberal views of a unitary dividing line between the two (looking specifically at Mill and Dewey). In the end, Geuss’ realist view is that deciding on a theoritically singular (and likely abstract) dividing line and then making political decisions gets things the wrong way around: we need to decide what concrete context private/public is necessary for, and then build on that basis. A very short book, but quite interesting.