I first wrote about John Pateman around this time last year, responding to one of his Open Shelf columns about what Pateman understands as the “true community-led library” (an example of the No True Scotsman fallacy). As I said in “Public Libraries, History, and the State”, Pateman isn’t exactly wrong in his understanding of Marxis theory (though I think his understanding of the concepts is simplistic), the problem is with his attempt to connect Marxist theory to his understanding, first, of how libraries currently are and, second, what need to be done to change them. Over the past year or so, Pateman has written in his column on many topics related to Marxism and libraries, public services, and organizational structure, and he has gathered those thoughts together into a co-authored piece in Public Library Quarterly called “Managing Cultural Change in Public Libraries”.

John Pateman wrote this article with Joe Pateman who, according to the author bio, is “currently undertaking a Masters Degree at the University of Nottingham, with a specific interest in the disciplines of Marxist political theory and International Political Economy (IPE)”. This co-authorship is felt, I think, in the weight given in the first half of the article to a reading of Maslow and Marx, using Marx as a way to correct Maslow’s “idealism”. Admittedly, this goes beyond the theoretical parts of John Pateman’s columns, but is still presented in an over-simplified manner, as if there has not been 150 years of debate, disagreement, formulations, and reformulations around what Marx and Engels meant and how this might be applied to a given historical moment. I can’t speak to the reception of Maslow, but I imagine there has been a lot of analysis and synthesis undertaken of his thinking since his hierarchy of needs first appeared in 1943. My issue is not so much with the interpretation of Marxism, though I find it oversimplistic and too black and white. For example, given the following statement:

This article combines the ideas of Karl Marx and Abraham Maslow and their theories of human needs to construct an Analytical Framework based on a specific interpretation of historical materialism known as technological/economic determinism. (1)

This confuses a few conceptual categories. There are many kinds of technological or economic determinism, and such a determinism is one possible criticism of historical materialism, but “technological/economic determinism” is not an interpretation of historical materialism. Indeed, few Marxists, I think, would agree that historical materialism is a determinism. In any event, this is the only mention of determinism, so it’s difficult to understand exactly what is meant by the term here, and how it connects Marx/Maslow with the Analytical Framework.

Another example is the use of Stalin’s Dialectical and Historical Materialism to support the idea that the relationship between the base and the superstructure is not unidirectional or directly causal. Many Marxist theorists have dug into this topic (Gramsci, Althusser, and Jameson to name just a few), but in addition, to simply cite Stalin in support of a view that “the superstructure can exercise an important role in shaping the base” undercuts the contention that the “interpretation” of historical materialism is a determinism - a deterministic position would argue precisely that the relationship between base and superstructure was unidirectional and causal. There is a contradiction in the theoretical component of the article.

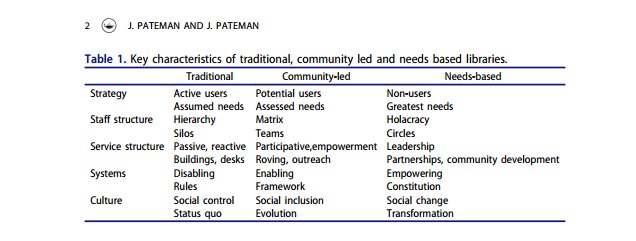

However, the main problem is with the sections on libraries, culled, it appears, from John Pateman’s columns. The “analytical framework” used in the article is simply offered without explanation. If the framework is analytical, what was the empirical basis for the characteristics?; without a discussion of where the characteristics used in the framework have come from, it appears as if the framework was put together based on anecdote (or, to be charitable, personal experience). In any event we don’t know.

Once again, I don’t particularly disagree with Pateman’s characterization of “traditional libraries”, but I don’t know where this characterization has been drawn from, which puts the other two categories - “community-led” and “needs-based” - on very shaky ground indeed, because they look like they have been invented for Pateman’s theoretical purpose, as models to be used to uphold his argument. This isn’t a bad thing in and of itself, but when they are present without justifcation or explanation in an analytical framework, they don’t seem to be based on anything. And when - as has been discussed before - Pateman uses a term (“community-led library”) that is more widely used to justify library budget cuts under neoliberal austerity, it muddies his methodology, and forces him back on the No True Scotsman fallacy, as mentioned above.

It is interesting, I think, that - while there are not many citations in the theoretical part of the article - there are no citations at all in the sections dealing with libraries. The argument isn’t backed up by anything, which allows Pateman to say whatever he likes about “community-led” and “needs-based” libraries. He is able to make them sound as if they exist in reality and are not merely models. This rhetorical move allows him to argue that these two kinds of non-traditional libraries are based on Marxist/Maslovian theory while not, in fact, showing that anywhere. A statement like this

The Culture ensures that the Library is continually evolving and changing for the better and the public library is an agent of social inclusion… (13)

looks like a statement of fact, when in fact it is a theoretical description of a model. As a result, Pateman is absolved of explaining how the following situation arises; he is able simply to propose that it does:

Things are done in a spirit of curiosity and exploiration, and there are no hard and fast rules, which makes them easy to change. Staff know why the guidelines exist, had a role in deciding them, and can put forward suggestions for changing them. This makes distributing authority easier because everyone is following the same framework. (13)

Again, this is a theoretical postulation of a model state of affairs rather than a description of fact. It ignores questions like, for example, how those with authority react to its distribution? Again, a statement like this one (about “needs-based” libraries) ignores the entrenchment of power relationships within an organization as well as the relationships of power and domination within society that work to ensure the maintenance of the status quo:

The Staff Structure is a Holacracy, which removes power from the management hierarchy and distributes it across clear roles, which can then be executed autonomously, without a micromanaging boss. (13)

No mention of funding bodies, fiduciary duty, the signing of paychecks, worker organization, etc, etc. For Pateman, the organization exists in a vacuum and there are - despite his insistence on the relevance of Marxist theory - no material obstacles to a rational restructuring of the organization. This absolves Pateman of the hard work of accomodating those obstacles within his model. (Aside: has anyone figured out what “non-users” means?)

Returning to the question of “determinism” (assuming that that is a theoretical construct worth attaching an argument to, the Patemans seem to disregard determinism (and historical materialism) completely when they state the following:

The Culture ensures that the Library is in a constant state of transformation and disruptive innovation and the public library is an agency of social change.

In what Marxist framework can culture ensure this? The role of culture in society and organizations was pretty much the entire Frankfurt School project, but there is no engagement with that work here.

It may seem as if I spend a lot of time arguing with Pateman’s approach. My issue is that I do see a valid place for Marxism in the deconstruction and (hopefully) reconstruction of libraries as institutions of social good, but in my view, Pateman uses an oversimplified Marxism to underpin a vision of libraries that is not, in the end, based on any material interpretation of the mode of production. In this he risks, in the language and characteristics of his proposed library models, reaffirming and further entrenching the values of neoliberalism and inscribing those values in the fabric of libraries themselves. I think this is inadvertent, I think he is arguing in good faith, and I’m sure that social justice is a goal of his. But I think that what he is arguing for and the way he argues for it risks reproducing the dominant neoliberal values and methods, if only accidentally.